Concierto de Aranjuez , who hasn’t repeatedly played it over and over!

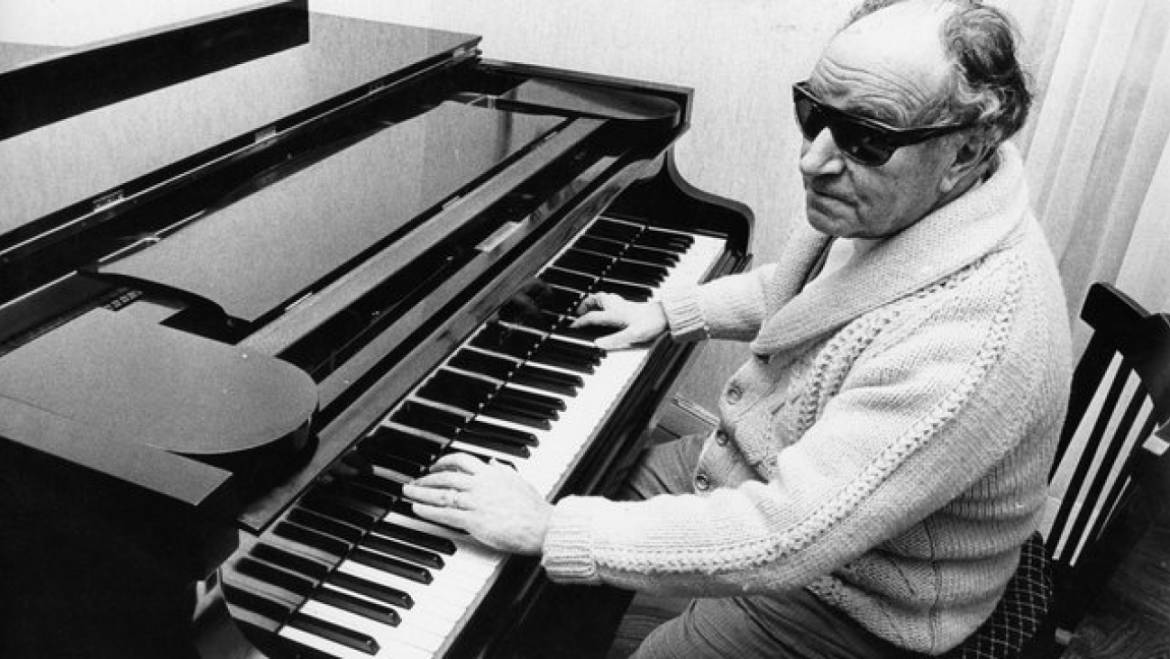

Joaquín Rodrigo (1901–1999) discovered a way of bringing Spanish music into the 20th century. His solution was to exploit singable melody and to use traditional orchestral timbres; or as the musicologist Tomas Marco puts it: “In form, harmony, melody and rhythm, Rodrigo’s work might be broadly classified as neo-classical”.

Back in Paris, the Rodrigos began to consider their definitive return to Spain, once the country was living in peace. On April 1st., 1939, the Spanish Civil War ended. Rodrigo received a letter from Manuel de Falla proposing a job as Professor of Music at the University of Granada or Seville. In addition, Antonio Tovar offered him a post in the Music Department of Radio Nacional in Madrid. They opted for the second offer. On September 4rd., 1939, two days after the Second World War broke out, they crossed the Spanish border. Within their meagre luggage, they carried with them the original manuscript in braille of Concierto de Aranjuez.

The Concierto de Aranjuez is a guitar concerto by the Spanish composer Joaquín Rodrigo. Written in 1939, it is by far Rodrigo’s best-known work, and its success established his reputation as one of the most significant Spanish composers of the 20th century.

This concerto is in three movements, Allegro con spirito, Adagio and Allegro gentile. The first and last movements are in D major, while the famous middle movement is in B minor. Along with the solo guitar, it is scored for an orchestra consisting of two flutes (one doubling on piccolo), two oboes (one doubling on cor anglais), two clarinets in B, two bassoons, two horns in F, two trumpets in C, and strings.

For a work as Spanish as Rodrigo’s Concierto de Aranjuez, it might seem bizarre that many people’s first encounter with it linked to Yorkshire. But the concerto’s use in the 1996 film Brassed Off! ensured that the popularity of this work sky-rocketed. The miners affectionately referred to it as ‘Orange Juice’, after finding it rather challenging to pronounce ‘Aranjuez’.

One of my most treasured possessions is a copy of the miniature score signed with a sweet inscription by the composer and dated April 6, 1993. Some guitarists have ventured to criticize Rodrigo’s scoring, though it would be difficult for them to tell what they would put in its place. Such criticism is like finding fault with the perfect action of a Swiss clock that has been keeping accurate time for half a century, or seeing imperfections in a painting by the French painter Jean-Antoine Watteau.

Of course, various mythologies have spun themselves around the creation of the Aranjuez—charming but highly questionable. One familiar fable, for example, is that Rodrigo and his wife Victoria de Kamhi spent their honeymoon in Aranjuez, Spain, and that was a large inspiration for the piece.

But when Rodrigo completed his new composition in 1939, he was in need of a title. He may have considered a resonant name from among the places the couple had visited five years previously. After Victoria’s experience of eating tripe, the concierto could hardly be named Concierto de Alcalá de Henares. Moreover, Concierto Escorial would celebrate a historical monument, but the place is formidably grim, different from the musical atmosphere evoked. Concierto de Toledo at that time would be too clearly political, following a famous siege there during the Spanish Civil War.

These days, Concierto de Aranjuez sits harmoniously on the Spanish tongue (though not easy for foreigners to pronounce!). Since the naming of the concerto and its extraordinary fame, a kind of cult has arisen round Aranjuez. The town is now presumed (especially by those who have not been there) to be the most enticing paradise in Spain. Yet an English writer, John Lomas, writing in 1902, commented that if the Spanish court were absent, Aranjuez was an “otherwise dull and monotonous place.”

Originally Posted on